White privilege

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

White privilege, or white skin privilege, is the societal privilege that benefits white people over non-white people in some societies, particularly if they are otherwise under the same social, political, or economic circumstances.[1][2] With roots in European colonialism and imperialism,[3] and the Atlantic slave trade, white privilege has developed[4] in circumstances that have broadly sought to protect white racial privileges,[5] various national citizenships, and other rights or special benefits.[6][7]

In the study of white privilege and its broader field of whiteness studies, both pioneered in the United States, academic perspectives such as critical race theory use the concept to analyze how racism and racialized societies affect the lives of white or white-skinned people.[8][9] For example, American academic Peggy McIntosh described the advantages that whites in Western societies enjoy and non-whites do not experience as "an invisible package of unearned assets".[10] White privilege denotes both obvious and less obvious passive advantages that white people may not recognize they have, which distinguishes it from overt bias or prejudice. These include cultural affirmations of one's own worth; presumed greater social status; and freedom to move, buy, work, play, and speak freely. The effects can be seen in professional, educational, and personal contexts. The concept of white privilege also implies the right to assume the universality of one's own experiences, marking others as different or exceptional while perceiving oneself as normal.[11][12]

Some scholars say that the term uses the concept of "whiteness" as a substitute for class or other social privilege or as a distraction from deeper underlying problems of inequality.[13][14] Others state that it is not that whiteness is a substitute but that many other social privileges are interconnected with it, requiring complex and careful analysis to identify how whiteness contributes to privilege.[15] Other commentators propose alternative definitions of whiteness and exceptions to or limits of white identity, arguing that the concept of white privilege ignores important differences between white subpopulations and individuals and suggesting that the notion of whiteness cannot be inclusive of all white people.[16][15] They note the problem of acknowledging the diversity of people of color and ethnicity within these groups.[15]

Some commentators have observed that the "academic-sounding concept of white privilege" sometimes elicits defensiveness and misunderstanding among white people, in part due to how the concept of white privilege was rapidly brought into the mainstream spotlight through social media campaigns such as Black Lives Matter.[17] As an academic concept that was only recently brought into the mainstream, the concept of white privilege is frequently misinterpreted by non-academics; some academics, having studied white privilege undisturbed for decades, have been surprised by the recent opposition from right-wing critics since approximately 2014.[18]

Definition

White privilege is a social phenomenon intertwined with race and racism.[1] The American Anthropological Association states that, "The 'racial' worldview was invented to assign some groups to perpetual low status, while others were permitted access to privilege, power, and wealth."[19] Although the definition of "white privilege" has been somewhat fluid, it is generally agreed to refer to the implicit or systemic advantages that people who are deemed white have relative to people who are not deemed white. Not having to experience suspicion and other adverse reactions to one's race is also often termed a type of white privilege.[2]

The term is used in discussions focused on the mostly hidden benefits that white people possess in a society where racism is prevalent and whiteness is considered normal, rather than on the detriments to people who are the objects of racism.[20][21] As such, most definitions and discussions of the concept use as a starting point McIntosh's metaphor of the "invisible backpack" that white people unconsciously "wear" in a society where racism is prevalent.[22][8][23]

History

European colonialism

European colonialism, involving some of the earliest significant contacts of Europeans with indigenous peoples, was crucial in the foundation and development of white privilege.[5][6] Academics, such as Charles V. Hamilton, have explored how European colonialism and slavery in the early modern period,[7] including the transatlantic slave trade and Europe's colonization of the Americas, began a centuries-long progression of white privilege and non-white subjugation.[4] Sociologist Bob Blauner has proposed that this era of European colonialism and slavery was the height, or most extreme version, of white privilege in recorded history.[24]

In British abolitionist and MP James Stephen's 1824 The Slavery of the British West Indies, while examining the racist colonial laws denying African slaves the ability to give evidence in West Indian jury trials; Stephen makes a clarifying distinction between masters, slaves, and "free persons not possessing the privilege of a white skin".[3]

In historian William Miller Macmillan's 1929 The Frontier and the Kaffir Wars, 1792–1836, he describes the motivations of Afrikaner settlers to embark upon the Great Trek as an attempt to preserve their racial privilege over indigenous Khoisan people; "It was primarily land hunger and a determination to uphold white privilege that drove the Trekkers out of the colony in their hundreds". Cape Colony was administered by the British Empire. Their increasingly anti-slavery policies were seen as a threat by the Dutch-speaking settlers, who were afraid of losing their African and Asian slaves and their superior status as people of European descent.[25] In 1932, Zaire Church News, a missionary publication in the Zaire area, confronted white privilege's impact from the European colonization of central and southern Africa, and its effects on black people's progress in the region:

In these respects the ambitions of profit-seeking Europeans, individually and especially corporately, may become prejudicial to the educational advance of the Congo people, just as white privilege and ambition have militated against Bantu progress on more than one occasion in South Africa.[26]

Scholar João Ferreira Duarte, in his jointedly written Europe in Black and White, has examined colonialism in relation to white privilege, suggesting its legacy continues "to imprint the privilege of whiteness onto the new map of Europe", but also "sustain the political fortification of Europe as a hegemonic white space".[27]

Early 20th-century

An address on Social Equities, from a 1910 National Council of the Congregational Churches of the United States publication, demonstrates some of the earliest terminology developing in the concept of white skin privilege:

What infinite cruelties and injustices have been practiced by men who believed that to have a white skin constituted special privilege and who reckoned along with the divine rights of kings the divine rights of the white! We are all glad to take up the white man's burden if that burden carries with it the privilege of asserting the white man's superiority, of exploiting the man of lesser breed, and making him know and keep his place.[28]

In his 1935 Black Reconstruction in America, W. E. B. Du Bois introduced the concept of a "psychological wage" for white laborers. He wrote that this special status divided the labor movement by leading low-wage white workers to feel superior to low-wage black workers.[29] Du Bois identified white supremacy as a global phenomenon affecting the social conditions across the world through colonialism.[30] For instance, Du Bois wrote:

It must be remembered that the white group of laborers, while they received a low wage, were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage. They were given public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white. They were admitted freely with all classes of white people to public functions, public parks, and the best schools. The police were drawn from their ranks, and the courts, dependent on their votes, treated them with such leniency as to encourage lawlessness. Their vote selected public officials, and while this had small effect upon the economic situation, it had great effect upon their personal treatment and the deference shown them. White schoolhouses were the best in the community, and conspicuously placed, and they cost anywhere from twice to ten times as much per capita as the colored schools. The newspapers specialized on news that flattered the poor whites and almost utterly ignored the Negro except in crime and ridicule.[29]

In a 1942 edition of Modern Review magazine, Ramananda Chatterjee accused Winston Churchill of hypocritical policy positions, in his support, as Chatterjee viewed it, of racial equality in the UK and US but not in British India; "Mr Churchill can support white privilege and monopoly in India whilst opposing privilege and monopoly on both sides of the Atlantic."[31] In 1943, during World War II, sociologist Alfred McClung Lee's Race Riot, Detroit 1943 addressed the "Nazi-like guarantee of white privilege" in American society:

White Americans might well ask themselves: Why do whites need so many special advantages in their competition with Negroes? Similar tactics for the elimination of Jewish competition in Nazi Germany brought the shocked condemnation of the civilized world.[32]

US civil rights movement

In the United States, inspired by the civil rights movement, Theodore W. Allen began a 40-year analysis of "white skin privilege", "white race" privilege, and "white" privilege in a call he drafted for a "John Brown Commemoration Committee" that urged "White Americans who want government of the people" and "by the people" to "begin by first repudiating their white skin privileges".[33] The pamphlet "White Blindspot", containing one essay by Allen and one by historian Noel Ignatiev, was published in the late 1960s. It focused on the struggle against "white skin privilege" and significantly influenced the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and sectors of the New Left. By June 15, 1969, The New York Times reported that the National Office of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was calling "for an all-out fight against 'white skin privileges'".[34] From 1974 to 1975, Allen extended his analysis to the colonial period, leading to the publication of "Class Struggle and the Origin of Racial Slavery: The Invention of the White Race"[35] (1975), which ultimately grew into his two-volume The Invention of the White Race in 1994 and 1997.[36]

In his work, Allen maintained several points: that the "white race" was invented as a ruling class social control formation in the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Anglo-American plantation colonies (principally Virginia and Maryland); that central to this process was the ruling-class plantation bourgeoisie conferring "white race" privileges on European-American working people; that these privileges were not only against the interests of African-Americans, they were also "poison", "ruinous", a baited hook, to the class interests of working people; that white supremacy, reinforced by the "white skin privilege", has been the main retardant of working-class consciousness in the US; and that struggle for radical social change should direct principal efforts at challenging white supremacy and "white skin privileges".[37] Though Allen's work influenced Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and sectors of the "new left" and paved the way for "white privilege" and "race as social construct" study, and though he appreciated much of the work that followed, he also raised important questions about developments in those areas.[38]

The modern understanding of 'white privilege' developed in the late 1980s, with Peggy McIntosh being considered one of the earliest exponents of the idea.[39]

Study of the concept

The concept of white privilege also came to be used within radical circles for self-criticism by anti-racist whites. For instance, a 1975 article in Lesbian Tide criticized the American feminist movement for exhibiting "class privilege" and "white privilege". Weather Underground leader Bernardine Dohrn, in a 1977 Lesbian Tide article, wrote: "... by assuming that I was beyond white privilege or allying with male privilege because I understood it, I prepared and led the way for a totally opportunist direction which infected all of our work and betrayed revolutionary principles."[40]

In the late 1980s, the term gained new popularity in academic circles and public discourse after Peggy McIntosh's 1987 foundational work "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack".[41][12] In this critique McIntosh made observations about conditions of advantage and dominance in the US.[42] She described white privilege as "an invisible weightless knapsack of assurances, tools, maps, guides, codebooks, passports, visas, clothes, compass, emergency gear, and blank checks", and also discussed the relationships between different social hierarchies in which experiencing oppression in one hierarchy did not negate unearned privilege experienced in another.[10][43] In later years, the theory of intersectionality also gained prominence, with black feminists like Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw arguing that black women experienced a different type of oppression from male privilege distinct from that experienced by white women because of white privilege.[44] McIntosh's essay is still routinely cited as a key influence by later generations of academics and journalists.[45][18]

In 2003, Ella Bell and Stella Nkomo noted that "most scholars of race relations embrace the use of [the concept] white privilege".[46] The same year, sociologists in the American Mosaic Project at the University of Minnesota reported that in the United States there was a widespread belief that "prejudice and discrimination [in favor of whites] create a form of white privilege." According to their poll, this view was affirmed by 59% of white respondents, 83% of Blacks, and 84% of Hispanics.[47]

21st-century popular culture

The concept of White privilege marked its transition from academia to more mainstream prominence through social media in the early 2010s, especially in 2014, a year in which Black Lives Matter formed into a major movement and the word "hashtag" itself was added to Merriam-Webster.[17] Brandt and Kizer, in their article "From Street to Tweet" (2015), discuss the American public's perception of the concept of privilege in mainstream culture, including white privilege, as being influenced by social media.[48]

Hua Hsu, a Vassar College professor of English, opens his New Yorker review of the 2015 MTV film White People by suggesting that white people have become aware of their privilege.[49] Hsu ascribes this to generational change, which he considers a byproduct of the "Obama era".[49]

The documentary White People, produced by Jose Antonio Vargas, follows a variety of white teenagers who express their thoughts and feelings about white privilege on-camera. Vargas interviews a white community college student, Katy, who attributes her inability to land a college scholarship to reverse racism against white people; then Vargas points out that white students are "40 percent more likely to receive merit-based funding".[50]

In January 2016, hip-hop group Macklemore and Ryan Lewis released "White Privilege II", a single from their album This Unruly Mess I've Made, in which Macklemore raps that he and other white performers have profited immensely from cultural appropriation of black culture, such as Iggy Azalea.[51]

According to Fredrik deBoer, it is a popular trend for white people to willingly claim self-acknowledgement of their white privilege online. deBoer criticized this practice as promoting self-regard and not solving any actual inequalities.[52] Michael J. Monahana argues that the rhetoric of privilege "obscures as much as it illuminates" and that we "would be better served by beginning with a more sophisticated understanding of racist oppression as systemic, and of individual agents as constitutively implicated in that system."[53][54]

A 2022 study found that mentioning white privilege results in online discussions that are "less constructive, more polarized, and less supportive of racially progressive policies."[55]

Applications in critical theory

Critical race theory

The concept of white privilege has been studied by theorists of whiteness studies seeking to examine the construction and moral implications of 'whiteness'. There is often overlap between critical whiteness and race theories, as demonstrated by focus on the legal and historical construction of white identity, and the use of narratives — whether legal discourse, testimony or fiction — as a tool for exposing systems of racial power.[56] Fields such as history and cultural studies are primarily responsible for the formative scholarship of critical whiteness studies.

Critical race theorists such as Cheryl Harris[57] and George Lipsitz[58] have said that "whiteness" has historically been treated more as a form of property than as a racial characteristic: in other words, as an object which has intrinsic value that must be protected by social and legal institutions. Laws and mores concerning race — from apartheid and Jim Crow constructions that legally separate different races to social prejudices against interracial relationships or mixed communities — serve the purpose of retaining certain advantages and privileges for whites. Because of this, academic and societal ideas about race have tended to focus solely on the disadvantages suffered by racial minorities, overlooking the advantageous effects that accrue to whites.[59]

Eric Arnesen, an American labor historian, reviewed papers from a whiteness studies perspective published in his field in the 1990s, and found that the concept of whiteness was used so broadly during that time period that it was not useful.[13]

Whiteness unspoken

From another perspective, white privilege is a way of conceptualizing racial inequalities that focuses on advantages that white people accrue from their position in society as well as the disadvantages that non-white people experience.[60] This same idea is brought to light by Peggy McIntosh, who wrote about white privilege from the perspective of a white individual. McIntosh states in her writing that, "as a white person, I realized I had been taught about racism as something which puts others at a disadvantage, but had been taught not to see one of its corollary aspects, white privilege which puts me at an advantage".[61] To back this assertion, McIntosh notes a myriad of conditions in her article in which racial inequalities occur to favor whites, from renting or buying a home in a given area without suspicion of one's financial standing, to purchasing bandages in "flesh" color that closely matches a white person's skin tone. According to McIntosh:

"[I see] a pattern running through the matrix of white privilege, a pattern of assumptions which were passed on to me as a white person. There was one main piece of cultural turf; it was my own turf, and I was among those who could control the turf. My skin color was an asset for any move I was educated to want to make. I could think of myself as belonging in major ways, and of making social systems work for me. I could freely disparage, fear, neglect, or be oblivious to anything outside of the dominant cultural forms. Being of the main culture, I could also criticize it fairly freely.[61]

Thomas K. Nakayama and Robert L. Krizek argued that one reason whiteness remains unstated is that whiteness functions as the presumed and invisible center of communication; it is only by making this center visible that the effects of white privilege can be examined.[62]

Unjust enrichment

Lawrence Blum refers to advantages for white people as "unjust enrichment" privileges, in which white people benefit from the injustices done to people of color, and he articulates that such privileges are deeply rooted in the U.S. culture and lifestyle:

When Blacks are denied access to desirable homes, for example, this is not just an injustice to Blacks but a positive benefit to Whites who now have a wider range of domicile options than they would have if Blacks had equal access to housing. When urban schools do a poor job of educating their Latino/a and Black students, this benefits Whites in the sense that it unjustly advantages them in the competition for higher levels of education and jobs. Whites in general cannot avoid benefiting from the historical legacy of racial discrimination and oppression. So unjust enrichment is almost never absent from the life situation of Whites.[15]: 311

Spared injustice

In Blum's analysis of the underlying structure of white privilege, "spared injustice" is when a person of color suffers an unjust treatment while a white person does not. His example of this is when "a Black person is stopped by the police without due cause but a White person is not".[15]: 311–312 He identifies "unjust enrichment" privileges as those for which whites are spared the injustice of a situation, and in turn, are benefiting from the injustice of others. For instance, "if police are too focused on looking for Black lawbreakers, they might be less vigilant toward White ones, conferring an unjust enrichment benefit on Whites who do break the laws but escape detection for this reason."[15]: 311–312

Privileges not related to injustice

Blum describes "non-injustice-related" privileges as those which are not associated with injustices experienced by people of color, but relate to a majority group's advantages over a minority group. Those who are in the majority, usually white people, gain "unearned privileges not founded on injustice."[15]: 311–312 According to Blum, in workplace cultures there tends to be a partly ethnocultural character, so that some ethnic or racial groups' members find them more comfortable than do others.[15]: 311–312

Framing racial inequality

Dan J. Pence and J. Arthur Fields have observed resistance in the context of education to the idea that white privilege of this type exists, and suggest this resistance stems from a tendency to see inequality as a black or Latino issue. One report noted that white students often react to in-class discussions about white privilege with a continuum of behaviors ranging from outright hostility to a "wall of silence".[63] A pair of studies on a broader population by Branscombe et al. found that framing racial issues in terms of white privilege as opposed to non-white disadvantages can produce a greater degree of racially biased responses from whites who have higher levels of racial identification. Branscombe et al. demonstrate that framing racial inequality in terms of the privileges of whites increased levels of white guilt among white respondents. Those with high racial identification were more likely to give responses which concurred with modern racist attitudes than those with low racial identification.[64] According to the studies' authors, these findings suggest that representing inequality in terms of outgroup disadvantage allows privileged group members to avoid the negative implications of inequality.[65]

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology had socially liberal people read about white privilege, and then read about a poor person who was either black or white. They found that reading about white privilege did not increase empathy for either, and decreased it if the person was white. One of the study's authors said that this demonstrates the importance of nuance, and recognizing individual differences, when teaching about white privilege.[66][67]

White privilege pedagogy

White privilege pedagogy has been influential in multicultural education, teacher training, ethnic and gender studies, sociology, psychology, political science, American studies, and social work education.[68][69][70]

Several scholars have raised questions about the focus on white privilege in efforts to combat racism in educational settings. Lawrence Blum says that the approach suffers from a failure to distinguish between factors such as "spared injustice" and "unjust enrichment".[15]

White fragility

Robin DiAngelo coined the term "white fragility" in the early 2010s, later releasing her 2018 book White Fragility.[71] She has said that "white privilege can be thought of as unstable racial equilibrium",[72] and that when this equilibrium is challenged, the resulting racial stress can become intolerable and trigger a range of defensive responses. DiAngelo defines these behaviors as white fragility. For example, DiAngelo observed in her studies that some white people, when confronted with racial issues concerning white privilege, may respond with dismissal, distress, or other defensive responses because they may feel personally implicated in white supremacy.[73][74] New York Times reporter Amy Harmon has referred to white fragility as "the trademark inability of white Americans to meaningfully own their unearned privilege".[75]

DiAngelo also writes that white privilege is very rarely discussed and that even multicultural education courses tend to use vocabulary that further obfuscates racial privilege and defines race as something that only concerns blacks. She suggests using loaded terminology with negative connotations to people of color adds to the cycle of white privilege.

It is far more the norm for these courses and programs to use racially coded language such as 'urban,' 'inner city,' and 'disadvantaged' but to rarely use 'white' or 'overadvantaged' or 'privileged.' This racially coded language reproduces racist images and perspectives while it simultaneously reproduces the comfortable illusion that race and its problems are what 'they' have, not us.[72]

She does say, however, that defensiveness and discomfort from white people in response to being confronted with racial issues is not irrational but rather is often driven by subconscious, sometimes even well-meaning, attitudes toward racism.[73] In a book review, Washington Post critic Carlos Lozada said that the book presents self-fulfilling and oversimplified arguments, and "flattens people of any ancestry into two-dimensional beings fitting predetermined narratives".[76]

White backlash

White backlash, the negative reaction of some white people to the advancement of non-whites, has been described as a possible response to the societal examination of white privilege, or to the perceived actual or hypothetical loss of that racial privilege.[77][78]

A 2015 Valparaiso University journal article by DePaul University professor Terry Smith titled "White Backlash in a Brown Country" suggests that backlash results from threats to white privilege: "White backlash—the adverse reaction of whites to the progress of members of a non-dominant group—is symptomatic of a condition created by the gestalt of white privilege".[79] Drawing on political scientist Danielle Allen's analysis that demographic shifts "provoke resistance from those whose well-being, status and self-esteem are connected to historical privileges of 'whiteness'",[80] Smith explored the interconnectivity of the concepts:

The hallmark of addiction is "protection of one's source." The same is true of backlash. The linear model of equality drastically underestimates the lengths to which people accustomed to certain privileges will go to protect them. It assigns to white Americans a preternatural ability to adapt to change and see their fellow citizens of color as equal.[79]

In Backlash: What Happens When We Talk Honestly about Racism in America, philosopher George Yancy expands on the concept of white backlash as an extreme response to loss of privilege, suggesting that DiAngelo's white fragility is a subtle form of defensiveness in comparison to the visceral racism and threats of violence that Yancy has examined.[81]

Global perspectives

White privilege functions differently in different places. A person's white skin will not be an asset to them in every conceivable place or situation. White people are also a global minority, and this fact affects the experiences they have outside of their home areas. Nevertheless, some people who use the term "white privilege" describe it as a worldwide phenomenon, resulting from the history of colonialism by white Western Europeans. One author states that American white men are privileged almost everywhere in the world, even though many countries have never been colonized by Western Europeans.[82][83]

In some accounts, global white privilege is related to American exceptionalism and hegemony.[84]

Africa

Namibia

The apartheid system in Namibia created the legal environment for establishing and maintaining white privilege. The segregation of peoples both preserved racial privileges and hindered unitary nation building.[85] In the period of years during the negotiation of Namibian independence, the country's administration, which was dominated by white Namibians, held control of power. In a 1981 NYT analysis, Joseph Lelyveld reported how measures which would challenge white privilege in the country were disregarded, and how politicians, such as Dirk Mudge, ignoring the policy of racial privilege, faced electoral threats from the black majority.[86] In 1988, two years before the country's independence, Frene Ginwala suggested that there was a general refusal to acknowledge the oppression of black women in the country, by the white women who, according to Ginwala, had enjoyed the white privilege of apartheid.[87]

Research conducted by the Journal of Southern African Studies in 2008 has investigated how white privilege is generationally passed on, with particular focus on the descendants of German Namibians, who arrived in the 1950s and 1960s.[88] In 2010, the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies further analyzed white privilege in post-colonial Namibia.[89]

South Africa

White privilege was legally enshrined in South Africa through apartheid. Apartheid was institutionalized in 1948 and lasted formally into the early 1990s. Under apartheid, racial privilege was not only socially meaningful—it became bureaucratically regulated. Laws such as the 1950 Population Registration Act established criteria to officially classify South Africans by race: White, Indian, Colored (mixed), or Black.[90]

Many scholars say that 'whiteness' still corresponds to a set of social advantages in South Africa, and conventionally refer to these advantages as "white privilege". The system of white privilege applies both to the way a person is treated by others and to a set of behaviors, affects, and thoughts, which can be learned and reinforced. These elements of "whiteness" establish social status and guarantee advantages for some people, without directly relying on skin color or other aspects of a person's appearance.[11] White privilege in South Africa has small-scale effects, such as preferential treatment for people who appear white in public, and large-scale effects, such as the over five-fold difference in average per-capita income for people identified as white or black.[91]

"Afrikaner whiteness" has also been described as a partially subordinate identity, relative to the British Empire and Boerehaat (a type of prejudice towards Afrikaners), "disgraced" further by the end of apartheid.[92] Some fear that white South Africans suffer from "reverse racism" at the hands of the country's newly empowered majority,[93] "Unfair" racial discrimination is prohibited by Section Nine of the Constitution of South Africa, and this section also allows for laws to be made to address "unfair discrimination". "Fair discrimination" is tolerated by subsection 5.[94]

Asia

Japan

Academic Scott Kiesling's co-edited The Handbook of Intercultural Discourse and Communication suggested that white English speakers are privileged in their ability to gain employment teaching English at Eikaiwa schools in Japan, regardless of Japanese language skills or professional qualifications.[95]

According to Japanese sociologist Itsuko Kamoro, White men represent the "apex" of romantic desirability to young Japanese women.[96] Many authors have described a widespread fetishization of White men by Japanese women, and cultural factors within Japan give white males a kind of 'gendered white privilege' that enables them to easily find a romantic partner.[96] According to other authors, many Japanese women are even willing to consider a white man who earns less money than them for marriage, which reflects the hegemonic masculinity of white men in Japan.[97] The same desirability is not given to white women within Japan, who are stereotyped as "mannish" or "loud", and therefore undesirable by Japanese men.[98]

South Korea

White privilege has been analyzed in South Korea, and has been discussed as pervasive in Korean society. White residents, and tourists to the country, have been observed to be given special treatment,[99] and, in particular, white Americans have been, at times, culturally venerated.[100]

Professor Helene K. Lee has noted that possessing mixed white and Korean heritage, or, specifically, its physical appearance, can afford a biracial individual white privilege in the country.[101] In 2009, writer Jane Jeong Trenka wrote that, as an adoptee to a white family from the United States, it was easier for her to recognize its function in Korean culture.[102]

The culture of US military camptowns in South Korea (a remnant of the Korean War) have been studied as a setting for white privilege, and an exacerbation of racial divides between white American and African American soldiers located on bases, as well as with local Korean people.[103]

North America

Canada

In 2014, the Elementary Teachers' Federation of Ontario received media coverage when it publicly advertised a workshop for educators about methods of teaching white privilege to students. "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack" had become one of its most recommended teaching tools.[104] During the 2014 Toronto mayoral election, then-candidate John Tory denied the existence of white privilege in a debate.[105][106]

In 2019, the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences suspended a man from attending their annual meeting for three years for racially profiling a black Canadian scholar. The federation stated that it required the offender to demonstrate that he had taken measures to increase his awareness of white privilege before he would be allowed to attend any future congress.[107]

Later in the year, a former First Nations in Manitoba grand chief stated how many indigenous Canadians perceived the court system of Canada to discriminate against them under the structure of white skin privilege.[108] Journalist Gary Mason has suggested that the phenomenon is embedded within the culture of fraternities and sororities in Canada.[109]

United States

Some scholars attribute white privilege, which they describe as informal racism, to the formal racism (i.e. slavery followed by Jim Crow) that existed for much of American history.[110] In her book Privilege Revealed: How Invisible Preference Undermines America, Stephanie M. Wildman writes that many Americans who advocate a merit-based, race-free worldview do not acknowledge the systems of privilege which have benefited them. For example, many Americans rely on a social or financial inheritance from previous generations, an inheritance unlikely to be forthcoming if one's ancestors were slaves.[111] Whites were sometimes afforded opportunities and benefits that were unavailable to others. In the middle of the 20th century, the government subsidized white homeownership through the Federal Housing Administration, but not homeownership by minorities.[112] Some social scientists also suggest that the historical processes of suburbanization and decentralization are instances of white privilege that have contributed to contemporary patterns of environmental racism.[113]

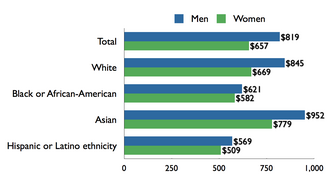

Wealth

According to Roderick Harrison "wealth is a measure of cumulative advantage or disadvantage" and "the fact that black and Hispanic wealth is a fraction of white wealth also reflects a history of discrimination".[114] Whites have historically had more opportunities to accumulate wealth.[115] Some of the institutions of wealth creation amongst American citizens were open exclusively to whites.[115] Similar differentials applied to the Social Security Act (which excluded agricultural and domestic workers, sectors that then included most black workers),[116] rewards to military officers, and the educational benefits offered to returning soldiers after World War II.[117] An analyst of the phenomenon, Thomas Shapiro, professor of law and social policy at Brandeis University, says, "The wealth gap is not just a story of merit and achievement, it's also a story of the historical legacy of race in the United States."[118]

Over the past 40 years, there has been less formal discrimination in America; the inequality in wealth between racial groups however, is still extant.[115] George Lipsitz asserts that because wealthy whites were able to pass along their wealth in the form of inheritances and transformative assets (inherited wealth which lifts a family beyond their own achievements), white Americans on average continually accrue advantages.[119]: 107–8 Pre-existing disparities in wealth are exacerbated by tax policies that reward investment over waged income, subsidize mortgages, and subsidize private sector developers.[120]

Thomas Shapiro wrote that wealth is passed along from generation to generation, giving whites a better "starting point" in life than other races. According to Shapiro, many whites receive financial assistance from their parents allowing them to live beyond their income. This, in turn, enables them to buy houses and major assets which aid in the accumulation of wealth. Since houses in white neighborhoods appreciate faster, even African Americans who are able to overcome their "starting point" are unlikely to accumulate wealth as fast as whites. Shapiro asserts this is a continual cycle from which whites consistently benefit.[121] These benefits also have effects on schooling and other life opportunities.[119]: 32–3

Employment and economics

Racialized employment networks can benefit whites at the expense of non-white minorities.[123] Asian-Americans, for example, although lauded as a "model minority", rarely rise to positions high in the workplace: only 8 of the Fortune 500 companies have Asian-American CEOs, making up 1.6% of CEO positions while Asian-Americans are 4.8% of the population.[124] In a study published in 2003, sociologist Deirdre A. Royster compared black and white males who graduated from the same school with the same skills. In looking at their success with school-to-work transition and working experiences, she found that white graduates were more often employed in skilled trades, earned more, held higher status positions, received more promotions and experienced shorter periods of unemployment. Since all other factors were similar, the differences in employment experiences were attributed to race. Royster concluded that the primary cause of these racial differences was due to social networking. The concept of "who you know" seemed just as important to these graduates as "what you know".

According to the distinctiveness theory, posited by University of Kentucky professor Ajay Mehra and colleagues, people identify with other people who share similar characteristics which are otherwise rare in their environment; women identify more with women, whites with other whites. Because of this, Mehra finds that white males tend to be highly central in their social networks due to their numbers.[125] Royster says that this assistance, disproportionately available to whites, is an advantage that often puts black men at a disadvantage in the employment sector. According to Royster, "these ideologies provide a contemporary deathblow to working-class black men's chances of establishing a foothold in the traditional trades."[123]

Other research shows that there is a correlation between a person's name and their likelihood of receiving a call back for a job interview. Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan found in field experiment in Boston and Chicago that people with "white-sounding" names are 50% more likely to receive a call back than people with "black-sounding" names, despite equal résumé quality between the two racial groups.[126] White Americans are more likely than black Americans to have their business loan applications approved, even when other factors such as credit records are comparable.[127]

Black and Latino college graduates are less likely than white graduates to end up in a management position even when other factors such as age, experience, and academic records are similar.[128][129][130]

Cheryl Harris relates whiteness to the idea of "racialized privilege" in the article "Whiteness as Property": she describes it as "a type of status in which white racial identity provided the basis for allocating societal benefits both private and public and character".[131]

Daniel A. Farber and Suzanne Sherry argue that the proportion of Jews and Asians who are successful relative to the white male population poses an intractable puzzle for proponents of what they call "radical multiculturism", who they say overemphasize the role of sex and race in American society.[132]

Housing

Discrimination in housing policies was formalized in 1934 under the Federal Housing Act which provided government credit to private lending for home buyers.[119]: 5 Within the Act, the Federal Housing Agency had the authority to channel all the money to white home buyers instead of minorities.[119]: 5 The FHA also channeled money away from inner-city neighborhoods after World War II and instead placed it in the hands of white home buyers who would move into segregated suburbs.[133] These, and other, practices intensified attitudes of segregation and inequality.

The "single greatest source of wealth" for white Americans is the growth in value in their owner-occupied homes. The family wealth so generated is the most important contribution to wealth disparity between black and white Americans.[119]: 32–33 [dubious – discuss] It has been said that continuing discrimination in the mortgage industry perpetuates this inequality, not only for black homeowners who pay higher mortgage rates than their white counterparts, but also for those excluded entirely from the housing market by these factors, who are thus excluded from the financial benefits of both capital appreciation and the tax deductions associated with home ownership.[119]: 32–3

Brown, Carnoey and Oppenheimer, in "Whitewashing Race: The Myth of a Color-Blind Society", write that the financial inequities created by discriminatory housing practices also have an ongoing effect on young black families, since the net worth of one's parents is the best predictor of one's own net worth, so discriminatory financial policies of the past contribute to race-correlated financial inequities of today.[134] For instance, it is said that even when income is controlled for, whites have significantly more wealth than blacks, and that this present fact is partially attributable to past federal financial policies that favored whites over blacks.[134]

Education

According to Stephanie Wildman and Ruth Olson, education policies in the US have contributed to the construction and reinforcement of white privilege.[135][136] Wildman says that even schools that appear to be integrated often segregate students based on abilities. This can increase white students' initial educational advantage, magnifying the "unequal classroom experience of African American students" and minorities.[137]

Williams and Rivers (1972b) showed that test instructions in Standard English disadvantaged the black child and that if the language of the test is put in familiar labels without training or coaching, the child's performances on the tests increase significantly.[138] According to Cadzen a child's language development should be evaluated in terms of his progress toward the norms for his particular speech community.[139] Other studies using sentence repetition tasks found that, at both third and fifth grades, white subjects repeated Standard English sentences significantly more accurately than black subjects, while black subjects repeated nonstandard English sentences significantly more accurately than white subjects.[140]

According to Janet E. Helms traditional psychological and academic assessment is based on skills that are considered important within white, western, middle-class culture, but which may not be salient or valued within African-American culture.[141][142] When tests' stimuli are more culturally pertinent to the experiences of African Americans, performance improves.[143][144] Critics of the concept of white privilege say that in K–12 education, students' academic progress is measured on nationwide standardized tests which reflect national standards.[145][146]

African Americans are disproportionately sent to special education classes in their schools, and identified as being disruptive or suffering from a learning disability. These students are segregated for the majority of the school day, taught by uncertified teachers, and do not receive high school diplomas. Wanda Blanchett has said that white students have consistently privileged interactions with the special education system, which provides 'non-normal' whites with the resources they need to benefit from the mainline white educational structure.[147]

Educational inequality is also a consequence of housing. Since most states determine school funding based on property taxes,[citation needed] schools in wealthier neighborhoods receive more funding per student.[148] As home values in white neighborhoods are higher than minority neighborhoods,[citation needed] local schools receive more funding via property taxes. This will ensure better technology in predominantly white schools, smaller class sizes and better quality teachers, giving white students opportunities for a better education.[149] The vast majority of schools placed on academic probation as part of district accountability efforts are majority African-American and low-income.[150]

Inequalities in wealth and housing allow a higher proportion of white parents the option to move to better school districts or afford to put their children in private schools if they do not approve of the neighborhood's schools.[151]

Some studies have claimed that minority students are less likely to be placed in honors classes, even when justified by test scores.[152][153][154] Various studies have also claimed that visible minority students are more likely than white students to be suspended or expelled from school, even though rates of serious school rule violations do not differ significantly by race.[155][156] Adult education specialist Elaine Manglitz says the educational system in America has deeply entrenched biases in favor of the white majority in evaluation, curricula, and power relations.[157]

In discussing unequal test scores between public school students, opinion columnist Matt Rosenberg laments the Seattle Public Schools' emphasis on "institutional racism" and "white privilege":

The disparity is not simply a matter of color: School District data indicate income, English-language proficiency and home stability are also important correlates to achievement ... By promoting the "white privilege" canard and by designing a student indoctrination plan, the Seattle School District is putting retrograde, leftist politics ahead of academics, while the perpetrators of "white privilege" are minimizing the capabilities of minorities.[158]

Conservative author Shelby Steele believes that the effects of white privilege are exaggerated, saying that blacks may incorrectly blame their personal failures on white oppression, and that there are many "minority privileges": "If I'm a black high school student today ... there are white American institutions, universities, hovering over me to offer me opportunities: Almost every institution has a diversity committee ... There is a hunger in this society to do right racially, to not be racist."[159][160]

Anthony P. Carnevale and Jeff Strohl show that whites have a better opportunity at getting into selective schools, while African Americans and Hispanics usually end up going to open access schools and have a lower chance of receiving a bachelor's degree.[161] In 2019, a National Bureau of Economic Research study found white privilege bias in Harvard University's application process for legacy admission.[162]

Military

In a 2013 news story, Fox News reported, "A controversial 600-plus page manual used by the military to train its Equal Opportunity officers teaches that 'healthy, white, heterosexual, Christian' men hold an unfair advantage over other races, and warns in great detail about a so-called 'White Male Club.' ... The manual, which was obtained by Fox News, also instructs troops to 'support the leadership of non-white people. Do this consistently, but not uncritically,' the manual states."[163] The manual was prepared by the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute, which is an official unit of the Department of Defense under the control of the Secretary of Defense.[164]

Oceania

Australia

Indigenous Australians were historically excluded from the process that lead to the federation of Australia, and the White Australia policy restricted the freedoms for non-white people, particularly with respect to immigration. Indigenous people were governed by the Aborigines Protection Board and treated as a separate underclass of non-citizens.[165] Prior to a referendum conducted in 1967, it was unconstitutional for Indigenous Australians to be counted in population statistics.

Holly Randell-Moon has said that news media are geared towards white people and their interests and that this is an example of white privilege.[166] Michele Lobo claims that white neighborhoods are normally identified as "good quality", while "ethnic" neighborhoods may become stigmatized, degraded, and neglected.[167]

Some scholars[who?] claim white people are seen presumptively as "Australian", and as prototypical citizens.[167][168] Catherine Koerner has claimed that a major part of white Australian privilege is the ability to be in Australia itself, and that this is reinforced by, discourses on non-white outsiders including asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants.[169]

Some scholars[who?] have suggested that public displays of multiculturalism, such as the celebration of artwork and stories of Indigenous Australians, amount to tokenism, since indigenous Australians voices are largely excluded from the cultural discourse surrounding the history of colonialism and the narrative of European colonizers as peaceful settlers. These scholars[who?] suggest that white privilege in Australia, like white privilege elsewhere, involves the ability to define the limits of what can be included in a "multicultural" society.[170][171][172] Indigenous studies in Australian universities remains largely controlled by white people, hires many white professors, and does not always embrace political changes that benefit indigenous people.[173][174][175][176] Scholars also say that prevailing modes of Western epistemology and pedagogy, associated with the dominant white culture, are treated as universal while Indigenous perspectives are excluded or treated only as objects of study.[175][177][178][179] One Australian university professor[who?] reports that white students may perceive indigenous academics as beneficiaries of reverse racism.[180]

Some scholars[who?] have claimed that for Australian whites, another aspect of privilege is the ability to identify with a global diaspora of other white people in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. This privilege contrasts with the separation of Indigenous Australians from other indigenous peoples in southeast Asia.[165][181] They also claim that global political issues such as climate change are framed in terms of white actors and effects on countries that are predominantly white.[182]

White privilege varies across places and situations. Ray Minniecon, director of Crossroads Aboriginal Ministries, described the city of Sydney specifically as "the most alien and inhospitable place of all to Aboriginal culture and people".[183] At the other end of the spectrum, anti-racist white Australians working with Indigenous people may experience their privilege as painful "stigma".[184]

Studies of white privilege in Australia have increased since the late 1990s, with several books published on the history of how whiteness became a dominant identity. Aileen Moreton-Robinson's Talkin' Up to the White Woman is a critique of unexamined white privilege in the Australian feminist movement.[168] The Australian Critical Race and Whiteness Studies Association formed in 2005 to study racial privilege and promote respect for Indigenous sovereignties; it publishes an online journal called Critical Race and Whiteness Studies.[185]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, a localized relationship to the concept, frequently termed Pākehā privilege,[186] due to the legacy of the colonizing European settlers, has developed.[187]

Academic Huia Jahnke's book Mana Tangata: Politics of Empowerment explored how European New Zealanders, in rejecting the 'one people' national narrative and embracing the label Pākehā ("foreigner"), has allowed space to examine white privilege and the societal marginalization of Māori people.[188] Similarly, Massey University scholar Malcolm Mulholland argued that "studying inequalities between Māori and non-Māori outcomes allows us to identify Pākehā privilege and name it."[189]

In their book Healing Our History, Robert and Joanna Consedine argued that in the colonial era Pākehā privilege was enforced in school classrooms by strict time periods, European symbols, and the exclusion of te reo (the Māori language), disadvantaging Māori children and contributing to the suppression of Māori culture.[190]

In 2016, on the 65th anniversary of Māori Women's Welfare League, the League's president criticized the "dominant Pakeha culture" in New Zealand, and embedded Pākehā privilege.[191]

See also

References

- ^ a b "References about social phenomena".

- Jensen, Robert (2005). "Race Words and Race Stories". The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism and White Privilege. City Lights Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 978-0872864498.

White privilege, like any social phenomenon, is complex.

- Monture, Patricia Anne; Patricia Danielle McGuire (2009). First Voices: An Aboriginal Women's Reader. Inanna Publications. p. 523. ISBN 978-0980882292.

Peggy Mcintosh's work on this issue, titled "White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack," remains one of the best resources for beginning to understanding this social phenomenon.

- Wise, Tim (2013). Kim Case (ed.). Deconstructing Privilege: Teaching and Learning as Allies in the Classroom. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 978-0415641463.

For example, I (Tim) often point to examples that illustrate such exceptions to highlight white privilege as a measurable social phenomenon even though poor White people exist.

- English, Fenwick W.; Cheryl L. Bolton (2015). "Chapter 2: Unmasking the School Asymmetry and the Social System". Bourdieu for Educators: Policy and Practice. SAGE Publications. p. 45. ISBN 978-1412996594.

Some educational researchers today have called this phenomenon "white privilege" (Apple, 2004; Swalwell & Sherman, 2012).

- Jensen, Robert (2005). "Race Words and Race Stories". The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism and White Privilege. City Lights Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 978-0872864498.

- ^ a b Neville, H., Worthington, R., Spanierman, L. (2001). Race, Power, and Multicultural Counseling Psychology: Understanding White Privilege and Color Blind Racial Attitudes. In Ponterotto, J., Casas, M, Suzuki, L, and Alexander, C. (Eds) Handbook of Multicultural Counseling, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- ^ a b Stephen, James (1824). The Slavery of the British West India Colonies Delineated. Cambridge University Press. p. 179.

- ^ a b Bischoff, Eva; Elisabeth Engel (2013). Colonialism and Beyond: Race and Migration from a Postcolonial Perspective. LIT Verlag. p. 33. ISBN 978-3643902610.

Whiteness scholars mostly concentrate on the idea of power as a white economic and political privilege, which is assumed to have been formed over centuries and to still be unconsciously perpetuated by individuals.

- ^ a b Hintzen, Percy C. (2003). Henke, Holger; Fred Reno (eds.). Modern Political Culture in the Caribbean. University Press of the West Indies. p. 396. ISBN 978-9766401351.

In making their claims to white elite status, the elite of colonial Africa and its colonized diaspora have managed to reproduce, in postcolonial political economy, the very forms of domination that existed under colonialism. These forms are rooted in racial exclusivity and racial privilege.

- ^ a b Henry, Frances; Carol Tator (2006). Racial Profiling in Canada: Challenging the Myth of 'a Few Bad Apples'. University of Toronto Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0802087140.

Whiteness studies analyse the link between white skin and the position of privilege operating in most societies, including those which have been subjected to European colonialism.

- ^ a b Talley, Clarence R. (2017). Theresa Rajack-Talley; Derrick R. Brooms (eds.). Living Racism: Through the Barrel of the Book. Lexington Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-1498544313.

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton in their book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, argue that the internal colonialism of the Black population occurs as the purposeful relegation of the Black population to inferior political and economic status both during and subsequent to slavery. From this perspective, white privilege emerges in American society because of the relations of colonialism and exploitation.

- ^ a b Banks, J. (2012). Encyclopedia of Diversity in Education. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 2300. ISBN 978-1-4129-8152-1.

- ^ Cole, Mike, 1946- (2008). Marxism and educational theory : origins and issues. London: Routledge. pp. 36–49. ISBN 978-0-203-39732-9. OCLC 182658565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b McIntosh, Peggy. "White privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2016. Independent School, Winter90, Vol. 49 Issue 2, p31, 5p

- ^ a b Vice, Samantha (September 7, 2010). "How Do I Live in This Strange Place?". Journal of Social Philosophy. 41 (3): 323–342. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9833.2010.01496.x.

- ^ a b Martin-McDonald, K; McCarthy, A (January 2008). "'Marking' the white terrain in indigenous health research: literature review" (PDF). Journal of Advanced Nursing. 61 (2): 126–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04438.x. PMID 18186904.

- ^ a b Arnesen, Eric (October 2001). "Whiteness and the Historians' Imagination". International Labor and Working-Class History. 60: 3–32. doi:10.1017/S0147547901004380. S2CID 202921126.

- ^ Hartigan, Odd Tribes (2005), pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Blum, Lawrence (2008). "'White Privilege': A Mild Critique 1". Theory and Research in Education. 6 (3): 309–321. doi:10.1177/1477878508095586. S2CID 144471761.

- ^ Forrest, James; Dunn, Kevin (June 2006). "'Core' Culture Hegemony and Multiculturalism" (PDF). Ethnicities. 6 (2): 203–230. doi:10.1177/1468796806063753. S2CID 16710756.

- ^ a b Brydum, Sunnivie (December 31, 2014). "The Year in Hashtags: 2014". The Advocate. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Weinburg, Cory (May 28, 2014). "The White Privilege Moment". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ American Anthropological Association (1998). "AAA Statement on Race". Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ Pulido, L. (2000). "Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California" (PDF). Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 90: 15. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.00182. hdl:10214/1833. S2CID 38036883.

- ^ Andersen, Chris (2012). "Critical Indigenous Studies in the Classroom: Exploring 'the Local' using Primary Evidence" (PDF). International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies. 5 (1). doi:10.5204/ijcis.v5i1.95.

- ^ Marcus, David (November 6, 2017). "A Conservative Defense of Privilege Theory". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018.

First described by Peggy McIntosh in the late 1980s, white privilege basically describes somewhat hidden advantages that white people in our society enjoy, that they did not earn. It absolutely describes an actual phenomenon. Her most basic examples ring true. White people do see themselves represented more often in our culture and history, and rarely are the only person who looks the way they do in rooms where power exists.

- ^ Lund, C. L. (2010). "The nature of white privilege in the teaching and training of adults". New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. 2010 (125): 18. doi:10.1002/ace.359.

- ^ Blauner, Bob (1972). Racial Oppression in America. HarperCollins. p. 26. ISBN 978-0060407711.

White privilege, while real and significant, is not as inherently crucial to our economic system and social life styles as it was in classical colonialism.

- ^ Macmillan, William Miller (1929). "The Frontier and the Kaffir Wars, 1792–1836". In John Holland Rose; Arthur Percival Newton; Ernest Alfred Benians; Henry Dodwell (eds.). The Cambridge history of the British Empire (Volume 8 ed.). The Macmillan company. p. 322.

- ^ Gliden Cram, Willard (1932). "Zaire Church News" (Volume 80-96 ed.). p. 16.

- ^ Sanches, Manuela Ribeiro; Fernando Clara; João Ferreira Duarte; Leonor Pires Martins, eds. (2011). Europe in Black and White: Immigration, Race, and Identity in the 'Old Continent'. IntellectBooks. p. 125. ISBN 978-1841503578.

- ^ Cady, George Luther (1910). "Social Equities". National Council Fourteenth Triennial Session Addresses and Discussions (October 10–20, Fourteenth Triennial Session ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: National Council of the Congregational Churches of the United States. p. 65.

- ^ a b Du Bois, W. E. B., Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 (New York: Free Press, 1995 reissue of 1935 original), pp. 700–701. ISBN 0-684-85657-3.

- ^ Leonardo, Zeus (2010). "The Souls of White Folk: critical pedagogy, whiteness studies, and globalization discourse". Race Ethnicity and Education. 5 (1): 2002. doi:10.1080/13613320120117180. S2CID 145354229.

- ^ Chatterjee, Ramananda (1942). "The Modern Review" (Volume 71 ed.). p. 20.

- ^ McClung Lee, Alfred; Norman Daymond Humphrey (1943). Race riot, Detroit 1943. University of Michigan: The Dryden Press. p. 139.

- ^ Allen, Theodore W., "A Call . . . John Brown Memorial Pilgrimage . . . December 4, 1965," John Brown Commemoration Committee, 1965 and Jeffrey B. Perry, "The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight against White Supremacy," Archived December 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine "Cultural Logic" 2010.

- ^ See Ignatin (Ignatiev), Noel, and Ted (Theodore W.) Allen, "'White Blindspot' and 'Can White Workers Radicals Be Radicalized?'" (Detroit: The Radical Education Project and New York: NYC Revolutionary Youth Movement, 1969); Thomas R. Brooks, "The New Left is Showing Its Age", The New York Times, June 15, 1969, p. 20; and Perry, "The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen. . . "

- ^ Allen, Theodore W., Class Struggle and the Origin of Racial Slavery: The Invention of the White Race Archived April 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine (Hoboken: Hoboken Education Project, 1975), republished in 2006 with an "Introduction" by Jeffrey B. Perry at Center for the Study of Working Class Life, SUNY, Stony Brook.

- ^ Allen, Theodore W., The Invention of the White Race, Vol. I: Racial Oppression and Social Control (New York: Verso, 1994, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84467-769-6) and Vol. II: The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America (New York: Verso, 1997, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84467-770-2).

- ^ Perry, Jeffrey B., "The Developing Conjuncture and Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy," Archived December 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine "Cultural Logic,'" July 2010, pp. 10–11, 34.

- ^ Allen, Theodore W., "Summary of the Argument of The Invention of the White Race", Part 1 Archived November 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, #8, Cultural Logic, I, No. 2 (Spring 1998), and Jeffrey B. Perry, "The Developing Conjuncture and Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy" Archived December 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Cultural Logic. July 2010, pp. 8, 80–89.

- ^ Nast, Condé; Rothman, Joshua (May 12, 2014). "The Origins of "Privilege"". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ Bennett, Jacob (May 2012), "White Privilege: A History of the Concept", Master's Thesis at Georgia State University.

- ^ Rothman, Joshua (May 13, 2014). "The Origins of "Privilege"". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- ^ McIntosh, Peggy (1988). "WHITE PRIVILEGE AND MALE PRIVILEGE: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women's Studies" (PDF). www.collegeart.org.

- ^ McIntosh, Peggy. White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women's Studies. Wellesley: Center for Research on Women, 1988. Print.

- ^ Thomas, Sheila; Crenshaw, Kimberlé (Spring 2004). "Intersectionality: the double bind of race and gender". Perspectives Magazine. American Bar Association. p. 2.

- ^ Crosley-Corcoran, Gina (May 8, 2014). "Explaining White Privilege to a Broke White Person". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Edmondson, Ella L. J.; Nkomo, Stella M. (2003). Our Separate Ways: Black and White Women and the Struggle for Professional Identity. Harvard Business Review Press. ISBN 978-1-59139-189-0.

- ^ "The Role of Prejudice and Discrimination in Americans' Explanations of Black Disadvantage and White Privilege" (PDF). American Mosaic Project. University of Minnesota. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ Brandt, Jenn; Kizer, Sam (2015). "From Street to Tweet". From Street to Tweet: Popular Culture and Feminist Activism. SensePublishers. pp. 115–127. doi:10.1007/978-94-6300-061-1_9. ISBN 978-94-6300-061-1. S2CID 155352216.

- ^ a b Hsu, Hua (July 30, 2015). "The Trouble with "White People"". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ Zimmeman, Amy (July 20, 2015). "'White People': MTV Takes On White Privilege". The Daily Beast. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

- ^ Jagannathan, Meera (January 22, 2016). "Macklemore slams Miley Cyrus, Iggy Azalea for appropriating black culture, tackles racism and Black Lives Matter in new track 'White Privilege II'". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ deBoer, Fredrik (January 28, 2016). "Admitting that white privilege helps you is really just congratulating yourself". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Suarez, Cyndi (March 26, 2019), "Putting 'Privilege' in Perspective", Non Profit Quarterly.

- ^ Monahana, Michael J. (March 17, 2014), "The concept of privilege: a critical appraisal", South African Journal of Philosophy.

- ^ Quarles, Christopher L.; Bozarth, Lia (May 4, 2022). "How the term "white privilege" affects participation, polarization, and content in online communication". PLOS ONE. 17 (5): e0267048. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1767048Q. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267048. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9067660. PMID 35507537.

- ^ See, for example, Haney López, Ian F. White by Law. 1995; Lipsitz, George. Possessive Investment in Whiteness; Delgado, Richard; Williams, Patricia; and Kovel, Joel.

- ^ Harris, Cheryl I. (June 1993). "Whiteness as Property". Harvard Law Review. 106 (8): 1709–95. doi:10.2307/1341787. JSTOR 1341787.

- ^ Lipsitz, George (2006). The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit From Identity Politics. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-493-9.

- ^ Lucal, Betsy (July 1996). "Oppression and Privilege: Toward a Relational Conceptualization of Race". Teaching Sociology. 24 (3): 245–55. doi:10.2307/1318739. ISSN 0092-055X. JSTOR 1318739. OCLC 48950428. S2CID 51912528.

- ^ Williams, Constraint of Race (2004), p. 11.

- ^ a b McIntosh, P. (1988). "White privilege: Packing the invisible backpack. p. 1

- ^ Nakayama, Thomas K.; Krizek, Robert L. (August 1995). "Whiteness: A strategic rhetoric". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 81 (3): 291–305. doi:10.1080/00335639509384117. ISSN 0033-5630.

- ^ Pence, Dan J.; Fields, J. Arthur (April 1999). "Teaching about Race and Ethnicity: Trying to Uncover White Privilege for a White Audience". Teaching Sociology. 27 (2): 150–8. doi:10.2307/1318701. ISSN 0092-055X. JSTOR 1318701. OCLC 48950428.

- ^ Branscombe, Nyla R.; Schmitt, Michael T.; Schiffhauer, Kristin (August 25, 2006). "Racial Attitudes in Response to Thoughts of White Privilege". European Journal of Social Psychology. 37 (2): 203–15. doi:10.1002/ejsp.348. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ Powell, Adam A.; Branscombe, Nyla R.; Schmitt, Michael T. (2005). "Inequality as Ingroup Privilege or Outgroup Disadvantage: The Impact of Group Focus on Collective Guilt and Interracial Attitudes" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 31 (4): 508–21. doi:10.1177/0146167204271713. PMID 15743985. S2CID 11601487. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Jilani, Zaid. "What Happens When You Educate Liberals About White Privilege?". Greater Good. Greater Good Science Center. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Cooley, Erin; Brown-Iannuzzi, Jazmin L.; Lei, Ryan F.; Cipolli, William (April 29, 2019). "Complex intersections of race and class: Among social liberals, learning about White privilege reduces sympathy, increases blame, and decreases external attributions for White people struggling with poverty". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 148 (12): 2218–2228. doi:10.1037/xge0000605. PMID 31033321. S2CID 139104272.

- ^ Rothenberg, Paula S., ed. (2015). White Privilege: Essential Readings on the Other Side of Racism (5th ed.). Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1429242202.

- ^ Gillespie, Diane (2003). "The pedagogical value of teaching white privilege through a case study". Teaching Sociology. 31 (4): 469–477. doi:10.2307/3211370. JSTOR 3211370.

- ^ Abrams, Laura S.; Gibson, Priscilla (2007). "Teaching notes: Reframing multicultural education: Teaching white privilege in the social work curriculum". Journal of Social Work Education. 43 (1): 147–160. doi:10.5175/JSWE.2007.200500529. S2CID 145640470.

- ^ Feminist, Anna Kegler; writer; Nerd, Messaging (July 22, 2016). "The Sugarcoated Language Of White Fragility | Huffington Post". The Huffington Post. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ a b DiAngelo, Robin (2011). "White Fragility". The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy. 3 (3): 54–70. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Waldman, Katy (July 23, 2018). "A Sociologist Examines the "White Fragility" That Prevents White Americans from Confronting Racism". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ Lopez, German (August 12, 2017). "The Charlottesville protests are white fragility in action". Vox. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ Harmon, Amy (October 8, 2019). "Prove You're Not White: For an Article About Race-Verification on Reddit, I Had an Unusual Request". The New York Times.

- ^ Lozada, Carlos (June 18, 2020). "White fragility is real. But 'White Fragility' is flawed". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Blasdel, Alex (April 24, 2018). "Is white America ready to confront its racism? Philosopher George Yancy says we need a 'crisis'". The Guardian.

- ^ Jaschik, Scott (April 24, 2018). "Backlash". Inside Higher Ed.

- ^ a b Smith, Terry (2015). "Valparaiso University Law Review: White Backlash in a Brown Country". 50 (1). Valparaiso University School of Law: 89–132.

Most importantly, voter suppression abets an addiction to white privilege—which is the source of white backlash—by advancing the idea that the voters who are prevented from accessing the polls were less worthy to vote in the first place.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Allen, Danielle (September 7, 2015). "Trump is tapping into a troubling US constituency". Business Insider.

- ^ Yancy, George (2018). Backlash: What Happens When We Talk Honestly about Racism in America. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 50. ISBN 978-1538104057.

The responses that I received, however, speak to something more extreme than just reactionary or unreceptive responses. Rather than "white fragility", these responses are ones that speak to deep forms of white world-making

- ^ Jacques, Martin (September 19, 2003), "The global hierarchy of race: As the only racial group that never suffers systemic racism, whites are in denial about its impact", The Guardian.

- ^ Merryfield, Merry M. (2000). "Why aren't teachers being prepared to teach for diversity, equity, and global interconnectedness? A study of lived experiences in the making of multicultural and global educators". Teaching and Teacher Education. 16 (4): 429–443. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00004-4.

Although white, middle class Americans may experience outsider status as expatriates in another country, there are few places on the planet where white male Americans are not privileged through their language, relative wealth and global political power.

- ^ Bush, Melanie E. L., "White World Supremacy and the Creation of Nation: 'American Dream' or Global Nightmare? Archived February 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine", ACRAWSA e-journal 6(1) Archived April 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, 2010.

- ^ Godfrey Mwakikagile (2015). Namibia: Conquest to Independence: Formation of a Nation. New Africa Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-9987160440.

The Apartheid system preserved white privilege in a divided society, segregated and invented divergent ethnic cultures and truncated the growth of a common national identity. Thus, Namibia lacked any facilitating conditions for unitary nation building

- ^ Joseph Lelyveld (June 17, 1981). "Council In Namibia Finds Whites' Grip Still Strong". The New York Times.

The new ministers find they can only make suggestions to the bureaucrats and the Administrator General and that when these suggestions touch on sensitive areas of white privilege, they tend to be shelved.

- ^ Maria Mboono Nghidinwa (2008). Women Journalists in Namibia's Liberation Struggle, 1985-1990. Basler Afrika Bibliographien. p. 46. ISBN 978-3905758078.

She further argues that due to the "white privilege" that white women enjoyed during apartheid Namibia, these white women generally also refused to acknowledge the oppression of black women and have generally failed to question their own status (Ginwala, 1988).

- ^ Heidi Armbruster (2008), 'With Hard Work and Determination You Can Make It Here': Narratives of Identity among German Immigrants in Post-Colonial Namibia (Volume 34 ed.), Journal of Southern African Studies: Taylor & Francis, pp. 611–628,

However, integration is largely sought in the social and symbolic context defined as 'German' and 'white', and in dissociation from Namibia as 'Africa'. Silences, ambivalences, and contradictions at the narrative level reveal these generational cohorts to be slightly different, yet equally evasive about the problematic inheritance of white privilege.

- ^ Heidi Armbruster (2010), 'Realising the Self and Developing the African': German Immigrants in Namibia (Volume 36 ed.), Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, pp. 1229–1246,

As Leonard (2010b) observes, since Western migrants in less developed countries enjoy certain privileges and status, the connotation of the word "expatriate" has evolved so that it now implies white privilege. For example, European immigrants still enjoy what they perceive to be favorable conditions in postcolonial Namibia, with many Namibians expressing gratitude for "the benefits of colonialism"

- ^ Deborah Posel, "Race as Common Sense: Racial Classification in Twentieth-Century South Africa", African Studies Review 44 (2), September 2001.

- ^ Matthews, Sally (September 12, 2011), "Inherited or earned advantage?", Mail & Guardian.

- ^ Steyn, Melissa E. (2004). "Rehabilitating a whiteness disgraced: Afrikaner white talk in post-apartheid South Africa". Communication Quarterly. 52 (2): 143–169. doi:10.1080/01463370409370187. S2CID 145673861.

- ^ Vice, Samantha (September 2, 2011), "Why my opinions on whiteness touched a nerve", Mail & Guardian.

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 - Chapter 2: Bill of Rights - South African Government". www.gov.za.

- ^ Paulston, Christina Bratt; Scott F. Kiesling; Elizabeth S. Rangel, eds. (2012). "Critical Approaches to IDC". The Handbook of Intercultural Discourse and Communication. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 98. ISBN 978-1405162722.

The privilege that White native-speaking English teachers have in Japan, as Kelly describes by drawing on Lummis (1977), indexes institutional racism. By virtue of being a White speaker of English, even if not a native English speaker, one has the privilege of obtaining employment to teach eikaiwa [English conversation] without professional qualifications or an ability to speak Japanese.

- ^ a b Debnár, M. (2016). Migration, Whiteness, and Cosmopolitanism: Europeans in Japan. Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-137-56149-7. Retrieved June 20, 2024.