The Cell (film)

| The Cell | |

|---|---|

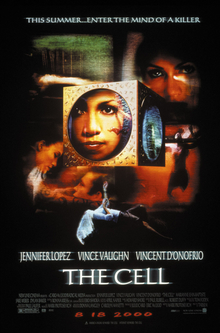

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tarsem Singh |

| Written by | Mark Protosevich |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Paul Laufer |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Howard Shore |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $33 million[2] |

| Box office | $104.1 million[2] |

The Cell is a 2000 science fiction psychological horror film directed by Tarsem Singh in his directorial debut, and starring Jennifer Lopez, Vince Vaughn, and Vincent D'Onofrio. The film follows scientists as they use experimental technology to enter the mind of a comatose serial killer in order to locate where he has hidden his latest kidnap victim.

The film received mixed reviews upon its release, with critics praising the visuals, direction, make-up, costumes and D'Onofrio's performance, while criticizing the plot, an emphasis on style rather than substance, and masochistic creation. Despite the critical reception, the film was a box office success, grossing over $104 million against a $33 million budget, and it earned a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Makeup.

Plot

[edit]Child psychologist Catherine Deane is hired to conduct an experimental virtual reality treatment for coma patients: a "Neurological Cartography and Synaptic Transfer System" device managed by doctors Henry West and Miriam Kent that allows her to enter a comatose mind and attempt to coax them into consciousness. The technology is funded by the parents of her patient, Edward Baines, a young boy left comatose by a viral infection that causes an unusual form of schizophrenia. Baines's progress has been hampered by a bogeyman-like alter ego whom Deane avoids. Despite Deane's lack of progress, West and Kent reject Deane's suggestion to reverse the feed to bring Baines into her mind, fearing the consequences of his experiencing an unfamiliar world.

Serial killer Carl Rudolph Stargher traps his victims in a cell-like glass enclosure that slowly fills with water by means of an automatic timer, then uses a hoist in his basement to suspend himself above their bodies while watching the recorded video of their deaths. He succumbs to the same schizophrenic illness and falls into a coma just as the FBI identifies him, leaving them without any leads as to the location of his latest victim, Julia Hickson. After learning of this experimental technology, Agent Peter Novak persuades Deane to enter Stargher's mind and discover Hickson's location.

Deane enters the dark dreamscape of Stargher's twisted psyche, filled with doll-like versions of his victims. Stargher's innocent side manifests as Young Stargher and leads Deane through his memories of abuse he suffered at the hands of his sadistic father. Deane nurtures Young Stargher in hopes of obtaining Hickson's location, but she is thwarted by another manifestation: King Stargher, a demonic idealization of his murderous side that dominates the dreamscape. King Stargher torments Deane until she forgets the world is not real. Dr. West discovers this while monitoring Deane's vitals. He warns that what happens to Deane while she is integrated into Stargher's mindscape will inflict neurological damage on her real body. Novak volunteers to enter Stargher's mind to make Deane remember herself.

Inside Stargher's mind, Novak is captured and subjected to King Stargher's torture while Deane looks on as Stargher's servant. Novak reminds Deane of a painful memory of her younger brother who died after a six-month coma due to a car accident during her college years to reawaken her awareness that she is in Stargher's mind. Deane breaks free of Stargher's hold and stabs King Stargher to free Novak. During their escape, Novak sees a version of the glass enclosure with the same insignia as the hoist in Stargher's basement. Novak's team discovers that after the hoist's previous owner went bankrupt, the government hired Stargher to seal up his property. Novak races to the property and finds Hickson treading water in the enclosure and breathing through a pipe. Novak breaks the glass wall and rescues Hickson.

Deane, now sympathetic to Young Stargher, locks her colleagues out and reverses the feed of the device to pull Stargher's mind into her own. She presents a comforting paradise to Young Stargher, but he knows it is only a temporary reprieve from King Stargher. He shifts to Adult Stargher to relate a childhood story of when he drowned an injured bird as a mercy killing to prevent its torture at his father's hands. King Stargher intrudes as a scaly snake-man, but this time, Deane is in control and she beats him to a bloody pulp before impaling him with a sword. However, Young Stargher exhibits the same injuries as King Stargher, and killing either manifestation kills Stargher. Adult Stargher reminds her of the story of the bird and implores her to "save" him. Deane carries Young Stargher into a pool, putting him out of his misery as Stargher dies in the real world.

In the aftermath, Deane and Novak meet outside of Stargher's house. The FBI has officially excluded the mind technology from their inquiry and Deane has gained approval to use the reverse feed on Edward Baines. Inside the paradise of Deane's mindscape, Baines walks to embrace Deane.[3]

Cast

[edit]- Jennifer Lopez as Dr. Catherine Deane

- Vince Vaughn as Special Agent Peter Novak

- Vincent D'Onofrio as Carl Rudolph Stargher

- Jake Thomas as young Carl Rudolph Stargher

- Marianne Jean-Baptiste as Dr. Miriam Kent

- Jake Weber as Special Agent Gordon Ramsey

- Dylan Baker as Henry West

- James Gammon as Teddy Lee

- Tara Subkoff as Julia Hickson

- Gerry Becker as Dr. Cooperman

- Dean Norris as Cole

- Musetta Vander as Ella Baines

- Patrick Bauchau as Lucien Baines

- Colton James as Edward Baines

- Catherine Sutherland as Anne Marie Vicksey

- Lauri Johnson as Mrs. Hickson

- Pruitt Taylor Vince as Dr. Reid

- Kim Chizevsky-Nicholls as Stargher's victim

- Gareth Williams as Stargher's father

- Peter Sarsgaard as John Tracy (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Filming

[edit]The scene where the Special Agents are trying to convince Dr. Catherine Deane to enter the killer's mind was recorded at the Barcelona Pavilion in Barcelona, Spain.

Artistic influences

[edit]Some of the scenes in The Cell are inspired by works of art. A scene in which a horse is split into sections by falling glass panels was inspired by the works of British artist Damien Hirst. The film also includes scenes based on the work of other late 20th century artists, including Odd Nerdrum, H. R. Giger and the Brothers Quay.[4] Tarsem—who began his career directing music videos such as En Vogue's "Hold On" and R.E.M.'s "Losing My Religion"—drew upon such imagery for Stargher's dream sequences. In particular, it has been speculated that he was influenced by videos directed by Mark Romanek, such as "Closer" and "The Perfect Drug" by Nine Inch Nails, "Bedtime Story" by Madonna,[5] and the many videos that Floria Sigismondi directed for Marilyn Manson. During a scene, Jennifer Lopez's character falls asleep watching a film; the film is Fantastic Planet (1973).

In the scene where Catherine talks with Carl while he is "cleaning" his first victim, the scenery resembles the music video "Losing My Religion" by R.E.M. The scene where Peter Novak first enters the mind of Carl Stargher, and is confronted by three women with open mouths to the sky, is based on the painting Dawn by Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum. The scene when Catherine is chasing Carl through a stone hallway, right before she enters the room with the horse, is based on the H. R. Giger painting "Schacht".

A psychiatrist entering the dreams of an insane patient in order to take control of the dreams and so to cure the patient's mind (this being a very risky attempt, because the insanity may prevail during such "neuro-participatory therapy") was described in the novella He Who Shapes (1965) by Roger Zelazny, but the film Dreamscape (1984), subsequently developed from Zelazny's basic idea, had a completely different plot.

Reception

[edit]Critical reaction to The Cell has been mixed. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 45% based on 166 reviews, with an average rating of 5.6/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "The Cell offers disturbing, stunning eye candy, but its visual pleasures are no match for a confused storyline that undermines the movie's inventive aesthetic."[6] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 40 out of 100, based on 32 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[7] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film a grade "C+" on scale of A to F.[8]

One of the most positive reviews came from Roger Ebert, who awarded the film four stars out of four, writing: "For all of its visual pyrotechnics, it's also a story where we care about the characters; there's a lot at stake at the end, and we're involved. I know people who hate it, finding it pretentious or unrestrained; I think it's one of the best films of the year."[9] Ebert later placed the film on his list of "The Best 10 Movies of 2000", writing: "Tarsem, the director, is a visual virtuoso who juggles his storylines effortlessly; it's dazzling, the way he blends so many notes, styles and genres into a film so original."[10] James Berardinelli gave the film three stars out of four, writing: "The Cell becomes the first serial killer feature in a long time to take the genre in a new direction. Not only does it defy formulaic expectations, but it challenges the viewer to think and consider the horrors that can turn an ordinary child into an inhuman monster. There are no easy answers, and The Cell doesn't pretend to offer any. Instead, Singh presents audiences with the opportunity to go on a harrowing journey. For those who are up to the challenge, it's worth spending time in The Cell."[11] Peter Travers from Rolling Stone wrote that "Tarsem uses the dramatically shallow plot to create a dream world densely packed with images of beauty and terror that cling to the memory even if you don't want them to."

Conversely, Stephen Hunter of The Washington Post called it "contrived", "arbitrary", and "overdrawn".[12] Slate's David Edelstein panned the film as well, writing: "When I go to a serial-killer flick, I don't want to see the serial killer (or even his inner child) coddled and empathized with and forgiven. I want to see him shot, stabbed, impaled, eviscerated, and finally engulfed—shrieking—in flames. The Cell serves up some of the most gruesomely misogynistic imagery in years, then ends with a bid for understanding."[13] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader remarked, "There's almost no plot here and even less character—just a lot of pretexts for S&M imagery, Catholic decor, gobs of gore, and the usual designer schizophrenia."[14] William Thomas of Empire gave the film two stars out of five, stating that "at times beautiful and always disturbing, this is strangely devoid of meaning."[15]

Sequel

[edit]A sequel was released direct to DVD on June 16, 2009. The story centers on The Cusp, a serial killer who murders his victims, and then brings them back to life, over and over again until they beg to die. Maya (Tessie Santiago) is a psychic investigator and surviving victim of The Cusp, whose abilities developed after spending a year in a coma. Maya must use her powers to travel into the mind of the killer unprotected, in order to save his latest victim.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Cell (2000)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "The Cell (2000)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Datlow, Ellen; Windling, Terri, eds. (2001). The Year's Best Fantasy and Horror: Fourteenth Annual Collection (14th ed.). New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. xc. ISBN 0-312-27544-7.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (August 18, 2000). "FILM REVIEW; Prowling the Corridors Of a Very Twisted Psyche". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Brevet, Brad (June 11, 2008). "Comparing Tarsem's 'Fall' and 'Cell' to Romanek's 'Bedtime Story'". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "The Cell". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ "The Cell". Metacritic.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 18, 2000). "The Cell". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 31, 2000). "The Best 10 Movies of 2000". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 26, 2020 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (2000). "Review: The Cell". Reelviews.

- ^ Hunter, Stephen (August 11, 2000). "Trapped in the Synapses of Evil". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017.

- ^ Edelstein, David (August 18, 2000). "Depth Psychology". Slate. Archived from the original on February 9, 2005.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "The Cell". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on August 14, 2006.

- ^ Thomas, William (2000). "The Cell Review". Empire. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

External links

[edit]- The Cell at IMDb

- The Cell at AllMovie

- The Cell at Box Office Mojo

- The Cell at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Cell at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- 2000 films

- 2000 crime thriller films

- 2000 directorial debut films

- 2000 horror films

- 2000 psychological thriller films

- 2000 science fiction films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s German films

- 2000s horror thriller films

- 2000s psychological horror films

- 2000s science fiction horror films

- 2000s science fiction thriller films

- 2000s serial killer films

- American crime thriller films

- American horror thriller films

- American psychological horror films

- American psychological thriller films

- American science fiction horror films

- American science fiction thriller films

- American serial killer films

- BDSM in films

- Crime horror films

- English-language German films

- Films about child abuse

- Films about nightmares

- Films about telepresence

- Films directed by Tarsem Singh

- Films scored by Howard Shore

- Films set underwater

- Films shot in Namibia

- German crime thriller films

- German horror thriller films

- German psychological thriller films

- German science fiction horror films

- German science fiction thriller films

- German serial killer films

- New Line Cinema films

- Science fiction crime films

- German psychological horror films

- English-language science fiction horror films

- English-language horror thriller films

- English-language science fiction thriller films

- English-language crime thriller films